Quotes & Notes: "The End of History and the Last Man", Francis Fukuyama

Greetings! I've finished another interesting book, and I'm sharing the parts that caught my attention.

The book is philosophical, so there won't be anything funny here. There's also a lot of text, but I've highlighted the most interesting moments, so if you don't have time or don't feel like reading everything — at least read what's in bold or italic.

I'll also mention up front that if I included a quote or an idea here, that doesn't mean I agree with it. It seemed like an interesting thought, something to ponder or argue about.

Although a lot of text will be quoted, this is just a tiny portion of the number of intriguing ideas in the book. So if something interests you, it's worth reading the whole book.

Read and quoted from the book "The End of History and the Last Man" by Francis Fukuyama, translated from English by M.B. Levin. - Moscow: AST: AST MOSCOW: KHRANITEL, 2007.

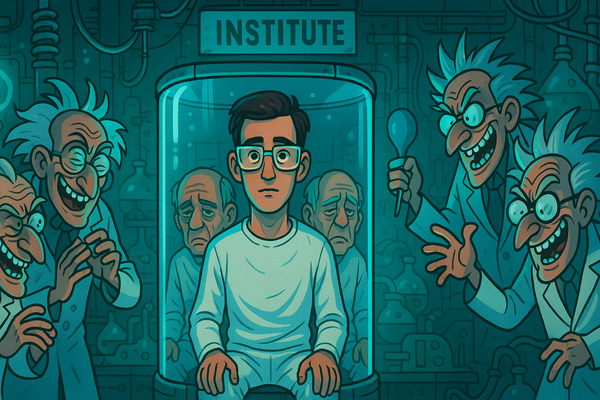

- Ken Kesey's novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, published in 1962, illustrates totalitarian hopes. The characters in the book are patients of a mental hospital, living an infantile and meaningless life under the supervision of the authoritative Big Nurse. The protagonist, McMurphy, tries to free them by breaking the hospital's rules and leading the inmate-patients toward freedom. But in the course of this attempt, he discovers that not a single one of them is being held in the hospital against their will. Ultimately, they all voluntarily remain within the hospital's walls under the controlling protection of the Big Nurse out of fear of the outside world. This was the ultimate goal of totalitarianism: not simply to deprive the new Soviet man of freedom but to make him fear freedom and, even without coercion, accept his chains as something benevolent.

- Many believed that the effectiveness of Soviet totalitarianism relied on the authoritarian traditions of the Russian people, which existed long before Bolshevism. A 19th-century European view of Russians, popularized by the French traveler Custine, described them as a people "devoted to slavery, who... only take terror and authority seriously." The Western belief in the stability of the Soviet system was based on the assumption—conscious or not—that the Russian people were not interested in democracy. After all, Soviet power wasn't imposed on the Russians by an external force in 1917, unlike Eastern Europe after World War II, and it survived for sixty to seventy years after the Bolshevik revolution, enduring famine, unrest, and invasion. This suggested that the system had gained a certain legitimacy among the masses and certainly within the ruling elite, as it reflected a natural inclination of society toward authoritarianism. Western commentators, who were quite ready to believe that the Polish people would want to throw off communism if given the chance, denied the same belief to the Russian people. In other words, they viewed Russians as the patients of a mental hospital, not restrained by bars or straitjackets, but by their longing for security, order, power, and other benefits the Soviet regime offered — such as imperial grandeur and superpower status. A strong Soviet state appeared very powerful, especially in the global strategic rivalry with the United States.

- There is an argument that even if communism is dead, it is quickly being replaced by intolerant and aggressive nationalism. It is premature to celebrate the demise of the strong state because, in places where communist totalitarianism didn't survive, it was simply replaced by nationalist authoritarianism or even fascism of the Russian or Serbian variety. In this part of the world, there will be neither peace nor democracy in the near future, and according to this view, it will pose as much danger to existing Western democracies as the Soviet Union once did.

- A liberal democratic state is weak by definition: safeguarding the sphere of individual rights means sharply limiting the state's power. Authoritarian regimes, both right-wing and left-wing, on the contrary, use state power to penetrate and control private life for various purposes—strengthening military power, building an egalitarian social order, or achieving rapid economic growth. What is lost in the realm of personal freedom must be gained at the level of national goals.

- Legitimacy is not justice or right in the absolute sense; it is a relative concept in people's subjective perceptions. All regimes capable of effective action must be based on some principle of legitimacy. No dictator rules solely by "force," as was often said about Hitler, for example. A tyrant can physically subdue his children, older people, and perhaps even his wife if he is physically stronger than them. Still, he is unlikely to be able to rule in the same way over two or three people, let alone a nation of millions. When we say that a dictator like Hitler "ruled by force," we mean that Hitler's henchmen — including the Nazi Party, the Gestapo, and the Wehrmacht — were able to physically intimidate the population. But why were these henchmen loyal to Hitler? Certainly not because of his ability to physically scare them: their loyalty was based on belief in his legitimate authority. Even a security apparatus can be managed through fear, but somewhere in the system, a dictator must have loyal subordinates who believe in the legitimacy of his rule. The same holds true even for the most corrupt mafia boss: he does not become a capo unless his "family" accepts his "legitimacy" on some basis. As Socrates explained in Plato's Republic, even among a band of robbers, there must be some principle of justice by which the loot is divided. Legitimacy, therefore, is the cornerstone even of the most unjust and bloodthirsty dictatorship.

- When we speak of a crisis of legitimacy in an authoritarian system, we are talking about a crisis among the elites, whose cohesion is the only thing that allows the regime to function.

- ... the standards of liberal democracy are the productivity of a market economy and the freedom of democratic politics.

- Political liberalism can be simply defined as the rule of law that recognizes certain individual rights or freedoms from government control. There are many definitions of fundamental rights, but we will choose the one found in Lord Bryce's classic book on democracy, where they are limited to three: civil rights — "freedom of the citizen from control over his person and property"; religious rights — "freedom to express religious views and perform worship"; and the rights the author calls political — "freedom from control in matters that do not directly affect the well-being of society as a whole in a way that would make control necessary" — this includes the fundamental right: freedom of the press.

- On the other hand, democracy is the right of all citizens without exception to be carriers of political power — that is, the right of all citizens to vote, be elected, and participate in politics. The right to participate in politics can be seen as another liberal right — of course, the most important one — and for this reason, liberalism and democracy have historically been firmly connected.

- Suppose we are now experiencing a moment when it is hard to imagine a world significantly different from ours, where there is no obvious or natural path by which the future will bring a fundamental improvement over the current order. In that case, we must allow for the possibility that History itself might have ended.

- The Universal History of humanity is not the same as the universe's history. It is not an encyclopedic catalog of everything known about humanity but an attempt to find a meaningful typical pattern in the development of human societies.

- Plato in the Republic speaks of a particular natural cycle of regimes; Aristotle in Politics discusses the causes of revolutions and why one regime replaces another. He believed that no regime can fully satisfy man, and dissatisfaction leads people to replace one regime with another in an endless cycle.

- Kant knew that "the idiotic course of all things human" has no visible pattern and that human history seems like a continuous chain of wars and cruelties. Yet he raised the question of whether there might be some regular movement in human history, which appears chaotic from the individual's point of view but in which a slow and progressive long-term tendency can be discerned. This was true, in particular, in the history of the development of human reason. For example, no individual could discover all of mathematics, but the cumulative nature of mathematical knowledge allowed each new generation to build upon the achievements of the previous ones.

- History moves forward through a continuous process of conflict, in which systems of thought, like political systems, clash and collapse due to their internal contradictions. They are then replaced by less contradictory and more advanced systems, which generate new and different inconsistencies — this is the so-called dialectic.

- "Eastern peoples knew that one man is free; the Greeks and Romans — that only some are free; whereas we know that all men are absolutely (man as such) free." For Hegel, the embodiment of human freedom was the modern constitutional state, or again, what we call liberal democracy.

- Hegel's Universal History considers not only the progress of knowledge and institutions but also the change in man's very nature because it is in man's nature not to have a fixed nature—not to be, but to become something other than what he was.

- The naive optimist, whose expectations are disappointed, looks foolish, whereas the pessimist, whose predictions do not come true, still appears serious and deep-thinking.

- Rousseau: All other desires of man are not essential for happiness; they arise from the ability of a person to compare himself with others and to consider himself deprived if he lacks what others have. These desires are created by modern consumerism — in other words, by human vanity, or what Rousseau himself calls human amour-propre. The problem here is that these new desires, created by man himself in historical times, are infinitely expandable and, in principle, impossible to satisfy. The modern economy, for all its incredible efficiency and innovation, creates a new desire for every fulfilled one, which must also be happy. People become unhappy not because they cannot meet a fixed set of desires but because there is always a gap between new desires and their fulfillment.

- The senseless destructiveness of the just-passed war will not necessarily teach people that no military technology can be used for reasonable purposes; new technologies may appear, and people will believe these provide a decisive advantage. Good countries, having learned the lesson of restraint taught by catastrophe and attempting to control the technologies that caused that catastrophe, will soon find themselves surrounded by bad countries that saw the catastrophe as an opportunity to pursue their own ambitions. And as Machiavelli taught at the beginning of the modern era, good states must learn from the bad to survive.

- According to the classical theory of free trade, participation in an open global trading system should provide maximum benefits for all, even if one country sells coffee beans and the other computers. Economically backward and late-entering countries should have some advantage in development since they can import technology from those who have already developed it rather than invent it themselves. The theory of dependency, on the other hand, claims that late development condemns a country to perpetual backwardness.

- Democracy ensures the participation of the people and thus provides feedback. Without it, states always tend to solve issues in favor of large enterprises that contribute substantially to national wealth rather than in favor of the long-term interests of dispersed groups of private citizens.

- Universal education produces middle-class societies. The link between education and liberal democracy has often been considered extremely important.

- For Hegel, the primary engine of human history is not modern science or the ever-expanding horizon of desires it fuels but a completely non-economic motive — the struggle for recognition.

- As Kojève explains, only a human can desire "an object completely useless from a biological point of view (for example, a medal or an enemy's flag). " He desires these objects not for their own sake but because they are desired by others.

- A "bloody battle" can have one of three outcomes. It may lead to the death of both combatants, in which case life itself — both natural and human — ends. It may lead to the death of one, leaving the survivor dissatisfied, as there is no longer another human consciousness to recognize him. Or finally, the battle may end in a master-slave relationship, when one combatant chooses a slave's life over the risk of violent death. After that, the master is satisfied because he risked his life and received recognition from another human being.

- By contrast, Hegel begins from a completely different understanding of man. Man is not defined by his animal or physical nature, and his very essence lies in overcoming or negating that nature. He is free in Hobbes's formal sense (absence of physical constraints) and in the metaphysical sense, as he is fundamentally indeterminate by nature.

- By risking his life, a man proves that he can act against the strongest and most basic instinct — the instinct for self-preservation. As Kojève puts it, man's human desire must prevail over his animal desire for self-preservation.

- Today, Thomas Hobbes is best known for two points: his characterization of the state of nature as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" and his doctrine of absolute sovereign monarchy, often unfavorably compared to Locke's more "liberal" affirmation of the right to revolution against tyranny. Hobbes was the first to establish that the legitimacy of rulers arises from the rights of the ruled, not from divine right or the natural superiority of those who govern.

- If people have no common master, the inevitable result is a war of all against all. The remedy for anarchy is government, founded on a social contract in which a person agrees "to give up this right to everything and be content with only as much liberty against others as he would allow them against himself." The only legitimate source of state power is its ability to protect and secure the rights individuals enjoy as humans. For Hobbes, the primary human right is the right to life — that is, the right of every person to protect their physical existence — and the only legitimate government is one that can adequately safeguard life and prevent a return to the war of all against all.

- Legitimate government arises from the need to protect man from his own violence.

- As Kant suggested, a liberal society could consist of devils, so long as they were rational.

- Thymos is something like an innate sense of justice in man: people believe they are worth something, and when others treat them as if they are worth less, they become angry when they do not acknowledge their proper value.

- When others notice that we do not live up to our self-assessment, we feel shame, and when we are judged relatively (i.e., in proportion to our true worth), we feel pride.

- Anger is the desire of desire — the desire for the person who undervalued us to change their opinion and recognize us in line with our self-esteem.

- However, recognition is not a "thing" like an apple or a Porsche; it is a state of consciousness, and to have subjective confidence in one's value, it must be acknowledged by another consciousness. Thus, thymos usually, though not necessarily, leads one to seek recognition.

- In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith argues that the reason people pursue wealth and avoid poverty has little to do with physical necessity. This is because "the wages of the lowest worker" can satisfy natural needs like "food and clothing, the comfort of housing, and the needs of the family" and because even people experiencing poverty spend most of their income on things that are, strictly speaking, "comforts that can be considered luxuries." So why do people strive to "improve their condition," throwing themselves into the hardships and bustle of economic life? Here's the answer:

- "To be noticed, to be the object of attention, to be met with sympathy, satisfaction, and approval — these are the advantages we propose. Vanity, not ease or pleasure, is what interests us. But vanity always rests on believing we are the objects of others' attention and judgment. The rich man delights in his wealth because he feels how it naturally draws the world's attention to him, and humanity is compelled to follow him in the pleasant emotions his elevated status so readily provokes... The poor man, by contrast, is ashamed of his poverty. He feels that it either removes him from humanity's view or, if he is noticed at all, it is rarely with sympathy for the humiliation and misery he endures..."

- Revolutionary situations cannot arise unless at least a handful of people are willing to risk life and comfort for a higher cause. The courage needed for this cannot come from the desiring part of the soul, but must arise from thymos. The man of desire — the Economic Man, the true bourgeois — will conduct internal "cost-benefit calculations" that will always give him a reason to "work within the system." Only the thymotic man — the man of anger, jealous of his own dignity and that of his fellow citizens, the man who feels that his value is more than a bundle of desires that make up physical existence — only such a person can stand in front of a tank or a line of soldiers.

- Today, Machiavelli is known above all as the author of brazen maxims about the brutal nature of politics — for example, that it is better to be feared than loved or that one should keep one's word only when it's advantageous. Machiavelli was the founder of modern political philosophy, and he believed that man could become the master of his earthly home if he based his actions not on how life should be, but on how it really is. Instead of trying to improve people through education, as Plato taught, Machiavelli sought a way to build a good political order from the corrupt nature of people: evil can be made to serve the purposes of good if it is channeled through the right institutions.

- After Machiavelli came another, perhaps more ambitious, project—one we're already familiar with. Hobbes and Locke, the founders of modern liberalism, sought to eliminate thymos from political life and replace it with a combination of desire and reason.

- The master is, in a sense, more human than the enslaved person, since he strives to overcome his biological nature for a non-biological goal — recognition. By risking his life, he demonstrates his freedom. The slave, by contrast, follows Hobbes's advice and submits to the fear of violent death. In doing so, he remains an animal, driven by fear and need, incapable of transcending biological or natural determinism. But this lack of freedom in the slave — his inferiority as a human being — is what creates the master's dilemma. The master needs recognition from another human being — that is, recognition of his value and human dignity by someone who also possesses value and dignity.

- This is the master's tragedy: he risks his life for recognition from an enslaved person who is unworthy of giving it.

- Modern science was not invented by idle masters who already had everything they wanted but by enslaved people who were forced to work and who disliked the existing conditions. Through science and technology, the slave realized that he could transform nature—not only the environment he was born into but also his own nature.

- A person gains satisfaction from owning property not only because it fulfills needs but also because others recognize it.

- Christianity places the realization of human freedom not in earthly life but in the coming Kingdom of Heaven. In other words, Christianity offers the correct concept of freedom but ends by calling on slaves to accept its absence and not expect liberation in this life. According to Hegel, Christianity fails to understand that it is not God who created man but man who created God. Man created God as a defense against the idea of freedom, seeing in the Christian God a being who is the ultimate master over himself and nature. But then the Christian submits to the God he just created.

- Thus, according to Hobbes and Locke, a liberal society is a mutual and equal agreement among citizens not to infringe upon one another's lives and property. Hegel, on the other hand, believes that a liberal society is a mutual and equal agreement among citizens for the mutual recognition of one another.

- Nationality is not a natural trait; a person has a nationality only if others recognize it.

- Recognition becomes mutual when the state and its people recognize one another — when the state guarantees citizens' rights and citizens agree to obey its laws.

- As stated earlier, there are no economic reasons for democracy; democratic politics, at best, is a burden on effective economics. Choosing democracy is a conscious choice, made for the sake of recognition, not the satisfaction of desires.

- Thus, the thirst for recognition is the missing link between liberal economics and liberal politics.

- In the preface to Philosophy of Right, Hegel explains that philosophy "is its own time grasped in thought," and the philosopher is no more able to step outside his own time and predict the future than a man can leap over the giant statue that once stood on the island of Rhodes.

- As Nietzsche said, "Every people speaks in its own language about good and evil," and "a people has found its language in its customs and laws," reflected not only in its constitution and laws but in family life, religion, class structure, daily habits, and ideals of lifestyle.

- The thirst for recognition is also the psychological foundation of two potent feelings — religion and nationalism. I do not mean to say that religion and nationalism can be reduced to the desire for recognition, but the roots of these passions in thymos give them such immense power. The believer attributes dignity to everything his religion considers sacred — a set of moral laws, a way of life, or specific objects of worship. And he becomes angry when the dignity of what he considers sacred is humiliated. The nationalist believes in the dignity of his national or ethnic group and, therefore, in his own dignity as a member of that group. He seeks recognition of that specific dignity from others and, like the religious believer, becomes angry when that dignity is degraded.

- Unlike money, which can be divided, dignity by its very nature does not allow compromise: either you recognize my dignity or the dignity of what I hold sacred — or you do not. Only thymos, seeking "justice," is capable of true fanaticism, obsession, and hatred.

- According to Hegel, work is the essence of man; the working enslaved person creates human history by transforming the natural world into a world inhabited by humans. Except for a handful of idle masters, all people work, yet there are striking differences in their manner of working and diligence. These differences are usually discussed under the term "work ethic."

- Traditional liberal economic theory, starting with Adam Smith, holds that work is essentially an unpleasant activity done only for the utility of the things it produces. This utility can mainly be enjoyed through idleness; in a sense, the goal of human labor is not to work but to be idle. People differ in productivity and in how burdensome they find work. Still, the point at which they stop working is the result of a rational calculation, where the burden of work is weighed against the pleasure gained from its results.

- "Democracy," claimed Lee, "is shackles on the legs of economic growth" because it hinders rational economic planning and promotes a kind of egalitarian indulgence of personal egoism, where myriad private interests assert themselves at the expense of society as a whole.

- All realist theories begin with the assumption that security threats are a universal and enduring feature of the international order, caused by its inevitably anarchic nature. In the absence of an international overlord, each state feels a potential threat from any other and has no other means to eliminate it than to arm itself for self-defense. This sense of threat is, in a sense, inevitable because every state will misinterpret the "defensive" actions of others as threatening to itself and take its own defensive measures, which in turn will be perceived as aggressive. Thus, the threat becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- Imperialism—the forceful domination of one community over another—arises directly from the aristocratic master's desire to be recognized as superior—that is, from his megalothymia.

- Kant's "First Definitive Article" for perpetual peace declares that the states forming the international system must be republics — liberal democracies. The "Second Definitive Article" affirms that "international law must be based on a federation of free states," states with republican constitutions. Kant's reasoning is straightforward: states based on republican principles are unlikely to wage war against each other since self-governing peoples are less willing to bear the costs of war than despotic regimes, and an effective international federation must be based on common liberal principles of law. International law is nothing more than domestic law rewritten on a larger scale.

- The post-historical world is one in which the desire for comfortable self-preservation has triumphed over the willingness to risk one's life in the battle for prestige and where the struggle for dominance has been replaced by universal and rational recognition.

- For Nietzsche, there was very little difference between Hegel and Marx because both aimed for a society to realize universal recognition. In fact, he raised the question: is recognition that can be universalized even worth attaining? Isn't the quality of recognition far more critical than its universality? And wouldn't the goal of universalizing recognition inevitably lead to its trivialization and devaluation?

- Nietzsche's "last man" is, essentially, the victorious enslaved person. Nietzsche entirely agrees with Hegel that Christianity is a slave ideology, and democracy is a secularized form of Christianity. "Equality of all men before the law" is the realization of the Christian ideal that all believers are equal in the Kingdom of Heaven. But the Christian belief in the equality of all people before God is nothing more than a prejudice born of the resentment of the weak toward those stronger than them. Christianity began by realizing that the weak could defeat the strong if they grouped into a herd and used the weapons of guilt and conscience. In modern times, this prejudice became widespread and irresistible, not because it turned out to be accurate, but because of the sheer number of weak people.

- The joke of Groucho Marx comes to mind — that he would never want to be a member of a club that would have him as a member: what is the worth of recognition given to everyone simply for being human?

- Successful action in life comes from a sense of self-worth, and if people are deprived of this sense, the belief in their own worthlessness becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- The point is that the desire to be recognized as superior by others is necessary if a person is to be superior to himself. Nietzsche noted that any form of actual excellence must originate in dissatisfaction, inner division of the self, and ultimately, war against oneself with all the suffering that entails: "One must have chaos in oneself to give birth to a dancing star." Good health and contentment with oneself are obstacles.

- In other words, modern education encourages tendencies toward relativism — the doctrine that all horizons and value systems are relative, tied to their place and time, and that no words are truths but only reflect the prejudices or interests of those who utter them. Relativism in this context leads not to the liberation of the great or the strong but only of the mediocre, who are now told they have nothing to be ashamed of.

____________________________________________________________________________

For those who want to donate, you can use PayPal (sashko1391@gmail.com) or send it directly to my card (4441111149739264).

All Ukrainian versions of my posts are available on Patreon, where they come first.