“Love Your Disease” or The Path of a Young Old Man

My own story of living with Parkinson`s disease.

“You have Parkinson’s disease,” — this was the conclusion of my second visit to a neurologist back in 2018. At the time, I didn’t know much about the disease — just that it was an illness of the elderly. Well, here I was, turned into an old man at 27 😁.

A Brief Introduction-Warning

I’m not a writer and have never written anything, so don’t expect a fully structured narrative here: plot, resolution, and whatever else? I graduated long ago and don’t remember the essentials 😑 Plus, I’m not much of a storyteller. I’m used to keeping everything to myself, processing what happens around me internally. Why burden others with your problems and thoughts (a flawed practice, as it turns out)? So, following the third aspect of Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path — right speech — I will be truthful in my story, avoiding unnecessary details, exaggerations, understatements, or embellishments.

First Symptoms

Let’s go back a few years, maybe three or four, to 2015. At the time, I didn’t give it much thought, but I remember it suddenly became inconvenient to carry my bag in my right hand, which I had always used. My arm stopped moving in sync with my walking (I’m clever enough to articulate this now; back then, it was just inconvenient). But it wasn’t a big deal—I simply switched the bag to my left hand🙂 Problem solved.

My friends (quite the jokers, though this story isn’t about them) noticed it too. They teased me about my “crab hand.” We chalked it up to overtraining at the gym — they claimed I was overworking the muscles. Problem solved again.

Over time, my handwriting became smaller and smaller. It had always been tiny (like many things I have 😅), but this was on another level — letters were barely 2–3 mm tall, and I couldn’t understand my own writing. But hey, it’s the 21st century — urbanization, digitization — all the perks of modern life, right? Indeed, my lack of handwriting practice was to blame.

One day in Odesa, I went to a registrar (an official handling property and company records) and needed to handwrite a statement. But I just couldn’t start. There was no pain or discomfort — my hand simply refused to work. It was as if I was looking at it — there it was, lying in front of me — but I couldn’t do anything with it. But yet again, I found an explanation. I had been drinking the day before! Indeed, this was just the aftermath of alcohol. And how we used to drink… That would require another story — a novel, maybe a trilogy.

For another six months, I delayed seeing a doctor — after all, my arm hadn’t fallen off, so why worry?

I started using my left hand more — for eating, washing, brushing my teeth, and, after a trip to the toile… Oh, what was I talking about? Right. My mom, a doctor by profession and calling, noticed these oddities and persuaded me to visit a neurologist at the city hospital. On my first visit, a doctor who seemed like she had been working since Khrushchev’s era prescribed an essential battery of tests. I underwent them, got an MRI, and received a diagnosis: “It’s just a feature of your body. No need to worry, no further testing required — just keep an eye on yourself.” What a brilliant analysis of my history and an excellent diagnosis! Universal, even. If you jot down all your complaints, I’m ready to give you the same conclusion — indeed, it would fit your situation. At least she didn’t use the term “vegetative-vascular dystonia.”

But things didn’t improve. Over a year or a year and a half, my arm became less and less responsive, and I found myself adapting to its dysfunction. I wasn’t overly worried, but not a day passed without thinking about that arm.

Naturally, I turned to the internet for information and advice. After five minutes of searching for symptoms, I suspected Parkinson’s disease. But there were too many nuances and diseases with similar symptoms. So, I decided to see another doctor for a paid consultation, this time a full-fledged professor of neurology.

The most phlegmatic old man reviewed my previous test results without ordering any new ones and concluded, “You have Parkinson’s disease.” For some reason, he decided to tell me about the horrifying consequences of the disease’s progression (Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disorder, meaning its symptoms constantly worsen). He said I was the youngest patient in his practice (I heard this many more times later — Yes, I’m a Champion! Love being the best!) and that I had about three years of normal life left. Where he got that number — only God knows.

Oh, and he decided to conduct a levodopa test.

So What is Parkinson’s Disease?

It seems like the time has come to delve a bit deeper into Parkinson’s disease (PD) to understand this story better. PD is a condition in which neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine gradually die off. Neurotransmitters are substances that transmit electrochemical impulses between cells in our bodies. A lack of dopamine leads to inhibitory effects of the basal ganglia (yes, we have those in our brain) on the central nervous system. In simple terms, muscles can quickly receive commands to contract, but they struggle to relax. This results in muscle rigidity, tremors, and postural instability (for starters).

Rigidity makes me move like C-3PO from Star Wars. Tremors? That’s when your limbs seem to dance and shake on their own as worshippers at the Embassy of God touched by Apostle Muntyan. And as for instability, the term speaks for itself — it’s hard to maintain balance.

You’d think the solution would be simple — just inject dopamine into the body, right? People with diabetes receive insulin regularly, after all! But no, our bodies have an interesting mechanism called the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This protective system prevents foreign substances from entering the nervous system and keeps internal substances from escaping. Wouldn’t it be nice if evolution created a similar barrier for brains to filter out propaganda?

Levodopa and Why I Dream of It

Now, let’s get back to levodopa. Since dopamine cannot cross the BBB, researchers discovered that levodopa — an amino acid — can. This substance is used in the treatment of PD. Actually, there isn’t a cure for PD yet (after all, funding research is boring; launching missiles at neighboring countries is more exciting!). However, levodopa temporarily alleviates motor symptoms. Thanks to this magical substance, I can write this story right now.

Levodopa enters the brain and miraculously serves as a precursor to dopamine. A little piece of it gets removed (scientifically called decarboxylation) and transforms into dopamine. Once there, it replenishes dopamine levels in the basal ganglia, providing a therapeutic effect.

The levodopa test works as follows: The patient’s motor functions are assessed using a special scale, they’re given a specific dose of a levodopa-containing medication (in my case, three tablets a day), and then re-evaluated to determine if there’s any improvement. If the result is positive, congratulations. If not, well, no congratulations; you likely have atypical parkinsonism, which doesn’t respond to levodopa.

I didn’t feel any effect. But then, how was I supposed to feel it if the disease was only beginning to manifest and I could still somewhat use my hand? Well, the neurologist concluded I had atypical right-sided parkinsonism. He prescribed some pills and sent me on my way.

So, I went to a third and then a fourth professor. The third one, the youngest of them all, ordered extensive tests to rule out other diseases. I’m grateful for that — we eliminated Wilson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, essential tremor, and more.

All in all, everyone confirmed the initial diagnosis: atypical parkinsonism. Let’s recall my second neurologist — the phlegmatic old man who told me how much time I had left and diagnosed me with atypical parkinsonism (remember the lack of response to levodopa?). Since the levodopa test is time- and labor-intensive, no one wanted to repeat it. And why would they do it if a professor had already performed it?

Subsequent doctors relied on the test results and based my treatment plan on these two assertions. That’s why I wasn’t prescribed any levodopa-containing medications. Instead, my doses of Neupro patches, pramipexole, and rasagiline tablets were gradually increased.

Symptom Progression and Support from Loved Ones

Over time, I started occasionally dragging my right leg, and my arm became increasingly “interesting.” Moving the mouse on my computer became difficult, so I switched to using the trackpad on my laptop with my left hand—problem solved. Typing on the keyboard also became more challenging, and everyday activities like cleaning the apartment, showering, and even driving ceased to bring enjoyment.

Others began noticing that something was wrong with me. That’s when my boss’s wife, Yulia, and his cousin, Natasha, stepped in, pushing me to try new treatments. I won’t mention my parents here — of course, they constantly demanded the same. To them, I always said, “Everything’s fine; everything’s under control.” But after consulting five professors and reading a ton of literature, I realized there wasn’t much I could cure. At best, I could manage the current symptoms temporarily. By that time, I was already taking three types of medications (technically, two types of pills and one patch-based medication).

I saw no point in visiting more professors. I hadn’t consulted with Professor Karaban or her student Slobodin. Still, I’d heard that the former was elderly and not great at communicating, while the latter was booked for the foreseeable future. There wasn’t much left to diagnose in Ukraine.

I’m surrounded by incredible people, and I’ve been undeniably lucky with my circle of support. My parents, brother, grandparents, ex-wife, daughter, and friends (I’ll write about them someday, too) are extraordinary.

Then there’s my boss. He’s the kind of person who deserves a book of his own — a unique individual. This story isn’t about him, but I’ll say a few words for context. He’s a true self-made man. Born in a village, he carved out his path, relying solely on himself. He has a phenomenal memory and is the kind of business partner everyone who’s worked with him wants to collaborate with again.

On my first day at work, he once gave me a ride home and asked, “Did you learn multiplication tables in school? Now, learn the division table.” By this, he meant that no one should be forgotten in any project and that profits should be distributed fairly.

He’s a mentor, an older brother, a godfather (he christened my beloved daughter), a friend, and a role model for me. He’s helped me countless times — getting into university, landing my first, second, and third jobs, buying a car, and providing me with housing (yeah). I’m not saying I’m dumb or lucky — far from it. I was an excellent student in school and university and always worked hard — sometimes even too hard (right, Katya?🙂). But no matter how smart you are, being in the right place at the right time is essential. My “right place” was my grandfather’s village, where my boss, a young man at the time, lived as my neighbor. As for timing, there were many key moments.

In Buddhism, there’s the concept of “perfect feeling,” one aspect of which is “dāna,” or giving. One type of dāna, the gift of fearlessness, is described as follows: “No, you cannot present someone with fearlessness on a platter or in a box tied with a ribbon. However, you can create a sense of fearlessness and security in others through your presence and position. Buddhism places great value on this ability to instill confidence in others through one’s presence, considering it an important contribution to society” (The Noble Eightfold Path by Sangharakshita, 1990).

This perfectly describes my boss. After every conversation with him, I always feel confident that everything will be fine, and I rush forward to face the future with renewed strength.

Conquering Berlin and German Testing

My boss gave me a contact for a company that organizes and accompanies foreigners during treatment in Germany. So, off I went to Berlin (I ended up going twice) to consult leading specialists in Parkinson’s and undergo a DAT scan. This scan evaluates the brain’s relationship with dopamine. Should I even mention who paid for this trip?..

I traveled to Germany with another good friend because traveling alone had become too uncomfortable at that stage of my illness. If my boss’s story were written as a book, it would resemble Dreiser’s The Financier. For my friend Andrey, it would be a Marvel-level Deadpool action movie — every day is an incredible story. How did we even survive to this age?

I must also credit my parents. Undoubtedly, I owe my good life to them, not only to my boss. I’ve mentioned that I grew up in an atmosphere of love and respect. My parents gave everything they could, allowing me to focus entirely on my studies without worrying about anything else.

A roof over my head (a big one, by the way), delicious food (not just for survival but the kind many have never tasted), and vacations (I traveled to many countries with my parents, some multiple times) were all provided by my mom and dad. I’ve also always been a fan of tech gadgets, and my parents indulged me in this non-essential hobby. Every six months, I got a new phone (back when not everyone even had one, let alone upgraded them). I had powerful computers, laptops, and musical equipment. My childhood was carefree and wonderful — thank you again, Mom and Dad.

Back to Germany

In 2019, the DAT scan confirmed I had Parkinson’s. When the doctor delivered the news, it was a funny moment. He expected me to be shocked, but I replied, “I already know,” since I had come to confirm the diagnosis, not to find out what disease I had.

The scanning procedure was quite interesting and worth mentioning. I was taken to a room with metal doors and numerous radiation hazard signs. Then, a nurse in a hazmat suit entered, carrying a lead case. From it, she took a syringe and successfully injected its contents into my vein.

After that, I was asked to walk outside for two hours, keeping my distance from people. Since my friend Andrey was waiting for me outside the office, he was told to maintain a distance. His response: “We have Chernobyl nearby; what do you think you’re scaring us with?” 🙂 We then went on a sightseeing spree around Berlin.

NB: I’m not one to dismiss safety measures — they’re essential. I’m just recounting how my friend reacted at the time.

My treatment plan was adjusted, and I was advised to return annually for follow-ups.

What Was Inside?

If you’re curious about my internal feelings upon realizing I had Parkinson’s at 27, the answer is simple — I didn’t experience any particular worries or regrets. Somehow, it coincided with a period when I had become deeply fascinated with Buddhism. Everything happening around me, I perceived with complete calmness.

I’m naturally an optimistic fool (in the best sense). I enjoy life, and I’m almost always in a good mood. I had just started earning money (thanks again, boss). I could afford to indulge in unnecessary purchases, both things and experiences. If I recall correctly, Erich Fromm’s book To Have or To Be inspired me not to regret money spent on experiences. Material things will age or break, but the emotions you’ve experienced remain with you as neural connections in your brain.

I won’t describe how we wandered around back then — I’ll leave that for another story :)

As time went on, my symptoms became more pronounced, and I had to adapt more and more. Of course, having money made things a little easier. For example, cleaning the apartment became harder — not a problem; I hired a cleaning lady. (Every time she came, I wondered why I hadn’t considered it before — it saved so much time and effort!) And there was plenty to clean — this was when I had separated from my wife, and my boss and his wife (yes, them again) allowed me to live in their old apartment, which was about 110 square meters — just for me.

After the War Began

Then came February 2024. Filthy, unwashed pigs broke out of their sty and onto the land of a young, well-kept European farm. Like in Orwell’s Animal Farm, they decided, “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others,” but they forgot they were still animals. Our country is home to free-spirited, brave, and wonderful people ready to “lay down their souls and bodies for our freedom.” The lines at enlistment offices were long, with people volunteering to fight.

Of course, the situation has since changed, but it’s worth remembering that the war has been ongoing for three years.

A heartfelt thank you to all our Heroes fighting an unequal battle against an inadequate, uneducated, and filthy enemy — both those alive and continuing the fight (Max P., Dima Y., Sergey B., Vitalik S. — hello) and those who have fallen (Max B., Alexei — hello to you too, perhaps you can still read this; I wouldn’t rule it out).

The War’s Impact on My Condition

With the war came complications in managing my illness. By that time, I’d been taking pills for years, but I was doing so mainly to feel like I was actively addressing the problem. I didn’t think the medication had any effect — or so I thought. Then the war began: shelling, fuel shortages, supply chain disruptions. Medications disappeared in Ukraine.

The patches stopped being supplied altogether, and the other pills required a 2–3 week wait. That’s when I realized the medications did have an effect. I finally understood the whole meaning of the terms “rigidity” and “akinesia.” My long-awaited right-hand tremor arrived.

Getting out of bed required mental preparation and earnest effort to signal my stiff muscles through synapses. I avoided eating with others because my hand wouldn’t lift properly, and eating looked, at best, strange. Even walking from my room to the café became a challenge. My right leg refused to cooperate and was reluctantly dragged behind the left.

Who do you think came to the rescue? You probably guessed almost right — almost, because it wasn’t the boss himself, but his wife, Yulia :) She somehow delivered me a whole package of precious patches. For the first time in weeks, I felt joy from ordinary movements more than from anything you’re “supposed” to enjoy.

During that three-week gap without patches, I only felt a spark of joy in March when my dad, godfather Sanya, his father-in-law, and I went to Kyiv to gather belongings. Our women had left for abroad, and the trip was full of lively conversations.

Smuggling Patches Across Borders

As I was writing this, I remembered how I got the patches and decided not to edit the previous part but to clarify here. The second patch was saved for a special occasion: helping my mom, daughter, and ex-wife escape abroad.

Back in school, I traveled to Spain through a government program and stayed with a Spanish family for about a month. These wonderful people found me on Instagram and offered to host my family during the war, or at least until the situation stabilized.

With this patch, I drove my loved ones to Hungary, where they boarded a plane to Barcelona. I then flew to Poland to meet my boss, where Yulia gave me three more packs of patches.

When I returned to Zakarpattia, my friend Sanya and I decided to share a room to save money. We had to sleep on one big bed, which was a nightmare for Sanya because my illness had practically robbed me of sleep. I sleep 2–3 hours a day, and poor Sanya spent a whole month searching for earplugs at every pharmacy in the area but never found any.

Life During Wartime

Those were interesting times, mainly because there wasn’t much to do—actually, nothing to do. Our only tasks for the day were to check if the nearby river was still there and kick the snow around. These tasks were usually completed by nine a.m., and we were left wondering what to do next.

Sleep and Parkinson’s

The situation with sleep is utterly unclear. Many people ask me if I feel like sleeping. No, I don’t. It’s not that I suffer because I can’t sleep — it’s just that I genuinely don’t want to. On the one hand, this is great because I have more time to live my life outside of sleep. On the other hand, it’s unclear where my body gets the resources to stay awake all the time.

The downside of this side effect is that if I suddenly feel sleepy, it happens abruptly, and I can fall asleep anywhere, at the most unexpected times. This can even occur while driving. So, if I sense that sleepiness is coming over me, I usually have about 1.5–2 minutes to pull over and wait it out. This “nap” usually lasts about 15–20 minutes.

There’s no point fighting this urge — it’s virtually irresistible. I don’t see dreams per se, but visions — a borderline state between sleep and wakefulness. Reality merges with what seems to me to be happening, and it gradually transitions into sleep. I narrowly avoided accidents a few times and realized that joking around with this wasn’t an option.

Traveling with Parkinson’s

Then, the one whose name I can’t mention anymore called me and said that I shouldn’t be idle in Zakarpattia and go abroad to be with my loved ones — and, if possible, show my daughter some other countries while the opportunity exists.

I won’t recount the adventures I faced in leaving the country for a second time because the game’s rules had changed in just one month. But I eventually managed to leave. It took me about 36 hours, and I ended up in Croatia through Hungary. The only detail worth mentioning is the jerk of a customs officer on the Hungarian side. They asked me to open my suitcases when I finally crossed the border. I did, and he didn’t like that there were a lot of women’s clothes.

I explained that I was transporting items for my mom, daughter, and wife, but he wasn’t satisfied and told me to unload everything onto a bench. I complied but warned him about my condition, explaining that I couldn’t repack the items independently, and asked for his help in advance. He agreed, but guess what — he turned around and walked off. Cursing and fuming, I managed to pile the items haphazardly onto the back seats and drove off. I hope he had diarrhea that evening :)

In Hungary, we stayed for about a month in a picturesque spot on the island of Vir before heading to Italy, where we stayed in three different places for two to three weeks each.

Discovering Italy

I never expected much from Italy. I’d always thought it was a classic European country, worth visiting only for its architecture — and that’s it. But after traveling from its top almost to its southernmost tip, I fell in love with its nature, especially Tuscany. It’s a wonderful country that now shares the top spot in my personal ranking with Norway.

I’m digressing — this story about my illness is turning into a travelogue, which is not the topic of discussion.

Katya prepared an extensive list of places to visit in every city we visited. You wouldn’t believe how meticulous she was — how much time dedicated to preparation and how thorough she was, just as she is in every aspect of her life. Katya analyzes everything to the fullest and makes well-thought-out decisions. On the opposite end of the decision-making spectrum is me: I act first and think later. I’m not sure which approach is better, but life is definitely easier with mine. :)

Walking through all these cities requires a lot of walking. I’d be in a lousy mood each morning because walking had become difficult. But, of course, I wanted to see such great cities. Often, this internal conflict spilled over into frustration, naturally directed at those around me — Katya and Ksusha (my daughter, the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen — and not just because I’m her father, but objectively!)

Looking back, I can say those were fantastic and eventful excursions with great company.

Returning to Kyiv and Moving to the Village

In July 2023, we returned to Ukraine, intending to stay for just two weeks to celebrate Ksusha’s birthday with our family before returning to Italy. However, within those two weeks, we realized Kyiv wasn’t as bad as we thought, so we decided to stay.

There’s not much to tell about my time in Kyiv. I lived with two friends, Zhenya and Sanya, who were constantly at my place. At some point, we were warned that the upcoming winter would be the harshest in Ukraine’s history. They said the Russians would destroy everything they could, and the winter promised to be cold and without electricity.

So, I decided to set up at least a stove in my grandfather’s house in the village to keep warm. This is the same village where my relatives went after the war began and where they all fell ill due to the lack of heating, proper electricity, and water. I bought a generator and two large power banks (or charging stations) and stocked up on firewood.

Thank God, the winter passed calmly. But by March, I felt resentful that I had done so much preparation and hadn’t used the house once. My friends and I decided to go to the village for two days for a barbecue. We arrived, grilled some food, and… chose to stay another week. A week later, we returned to Kyiv, packed our things, and went back to the village — this time for two weeks.

It’s been two years since I’ve been here. The recommendation to move here once again came from the one whose name I can’t mention, and it was the right decision.

Life in the Village

In Kyiv, with Parkinson’s, you might as well hang yourself. You wake up, walk to the kitchen, eat, walk to the hall, play Xbox, eat again, and lie down. With a broken motor system, the lack of movement is devastating.

In the village, on the other hand, there’s always something to do. At the very least, you must step outside and walk there to go to the bathroom. (“Dear guests, don’t poop on the board, aim for the hole — it’s unpleasant to clean up.” Grandma would have appreciated that note.)

There’s a forest and a river — you can swim or bike ride. The air is much cleaner. In short, it’s all positive. Plus, I wasn’t working much in Kyiv anymore since traveling to meetings was uncomfortable, and people pitied me and didn’t send me to them. But in the village — it’s perfect.

It’s even busier in winter: you have to heat both the first and second floors, so your muscles are constantly engaged. And that’s a big plus.

Life Today

I’m 33 now, and my typical day looks like this:

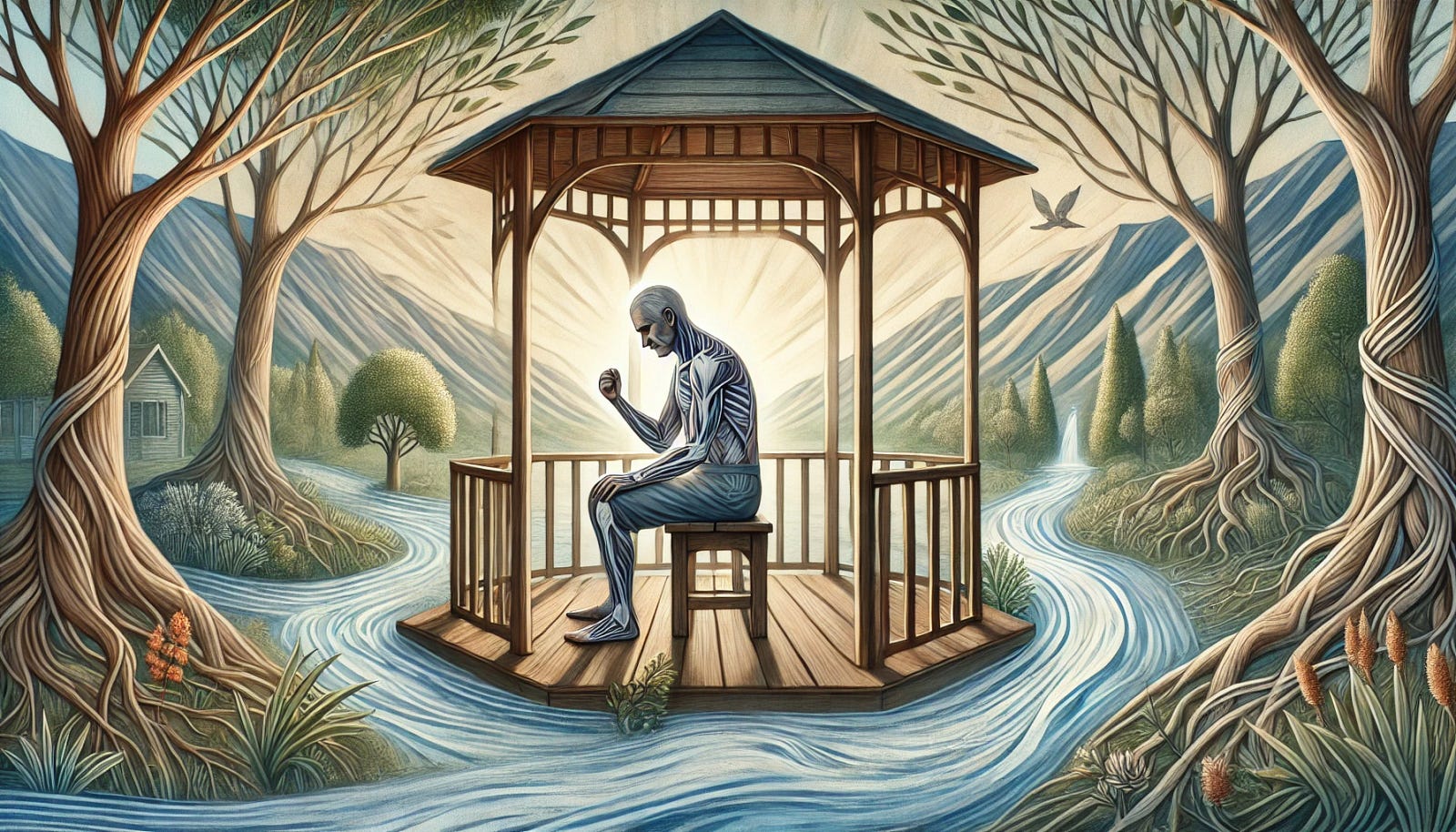

At 6 a.m., I take my first dose of medication. By 8, it kicks in; by 9:30, it wears off. At 10 a.m., I take the second dose, then at 2 p.m., and again at 6 p.m. Sometimes, the medication works for an hour and a half. Still, there are days when they don’t work at all. After all this time, I still haven’t found any patterns or correlations between the duration of these “on” and “off” periods and factors like food, weather, or mood. I accept it as a fact: if it kicks in, I rush to be active and get things done; if it doesn’t, I sit in the gazebo, staring at the ceiling.

During these “off” periods, I can only manage to watch a movie or YouTube since playing on a console or computer is no longer an option. Have your hands frozen so severely in the cold that your fingers won’t move? That’s close to how it feels.

Why do I use the terms “on” and “off”? Because that’s how it’s described in medical literature, and that’s exactly how it feels. I can sit like a statue, and then, within 10–15 seconds, I move normally. The reverse happens as suddenly: you’re walking or doing something, and — click — you’re down, forced to sit or fall. Like the cartoon, “When I’m nervous, I forget how to stand.”

Dyskinesia: A New Challenge

About nine months ago, dyskinesia started to appear. You know what a cramp feels like, right? Now imagine both antagonist muscles (e.g., biceps and triceps) cramping simultaneously — not for a minute or two but for 20–30 minutes. Then imagine that happening to your entire leg — quadriceps, calf, foot muscles — all pulling in different directions, trying to twist your leg every which way. What joy! But when the spasm finally subsides, the simple relaxation of a muscle feels like a blessing.

On the bright side, I don’t need to train my leg muscles — they get enough workouts during these episodes! Currently, these attacks happen about once every 2–3 days, but just two days ago, I had three in a single day.

If you’re thinking of suggesting pricking the muscle with a needle to release the cramp — don’t. The nature of these contractions is different. A regular cramp is an involuntary muscle contraction, while dystonia is caused by false signals from the brain. Unless you’re thinking of poking the brain with a needle…

Speaking of brains, this reminds me of DBS (deep brain stimulation). It’s like a pacemaker for the brain: a chip is implanted, wires run down the neck to the chest, and a battery is placed there. A minimalist Tony Stark, so to speak.

I consulted a doctor about it, but given my symptoms, it’s not suitable. DBS primarily alleviates tremors, while my main issue is stiffness.

Another consequence of Parkinson’s is speech impairment during “off” periods. I used to talk as fast as Usain Bolt ran, but now my speech can become slurred and mumbled to the point that I don’t understand myself. The best option during these times is to stay silent — you’ll seem smarter anyway.

The Side Effects of Medication

Parkinson’s medications, especially levodopa, come with a slew of side effects. I’ve never seen such a comprehensive list of adverse effects (though, to be fair, I never read instructions before this). Here’s a snippet from one of the first sites I came across:

“Levodopa/carbidopa most commonly causes side effects due to the central neuropharmacological activity of dopamine: dyskinesias (including choreiform movements), dystonic and other involuntary movements, and nausea. Muscle twitching and blepharospasm may be early signs to reduce the drug dose. Other serious side effects include mental changes, such as paranoid thinking, psychosis, depression with or without suicidal tendencies, dementia, sleep disturbances, psychotic episodes (including delusions, hallucinations, reduced cognitive ability, depression with or without suicidal tendencies, confusion, insomnia, anxiety, changes in mental status, including impulse control disorders such as pathological gambling, increased libido, hypersexuality, possible symptoms of impulse control disorders, and compulsive behaviors (overeating, oniomania — an impulsive desire to shop). Whew, I’m on fire! Write in the comments which side effects you would choose for yourself. Just kidding. 😄

Learning from Mistakes

These side effects have collectively led me to debts of about $80,000. I won’t specify which side effects are to blame, but there are many.

At the start of last year, I was hit by a wave of dark thoughts. I figured that I should make the most of it while I could still move. So, I started spending borrowed money on unnecessary things and making pointless investments, hoping to repay everything with projects I was involved in. But things didn’t go as planned. Drinking was also involved, which only worsened the situation.

A Fresh Start

By September, I had accumulated a mountain of problems, trying to cover old debts with new ones and seeing no way out. That’s when my boss stepped in again, gave me a “long and unpleasant” talk, and put my head back in place.

I’m writing this story at this point in my journey. For the past two months, I haven’t been drinking (okay, maybe a couple of times, but I’m trying not to exaggerate here). I’ve switched from cigarettes to IQOS, I train daily, and I bathe in the lake (sometimes in a tub outdoors, where the water is even colder). I’m rereading a book on Buddhism, refreshing the feelings I had when I first read it and clearing my mind again.

I’ve realized I have many friends who have helped and supported me financially, some with advice and others just by visiting. Thank you to all of you.

Moving Forward

I’m now experimenting with my body — I’ve found that cold water extends “on” periods. Who knows, maybe I’ll discover other patterns? I also plan to lose weight (I’m a 110-kilogram piglet) and try eating without meat for a while.

Perhaps the most important thing I’ve realized is that any illness, condition, or life situation is not a sentence — it’s a challenge. They may disrupt your life and alter your plans, but they cannot take away the most important thing: the right to choose how to respond to them.

No one knows how much time we have, especially during a war. But I know we should spend it actively, with a smile, trying new things, gratefully accepting help from friends, and supporting those facing difficulties.

Every new day is a chance to move forward, improve ourselves, and find joy even in the little things. Life is beautiful in its unpredictability, and if we learn to love even our weaknesses, we’ll become stronger than ever.

As Les Podervianskyi, a modern Ukrainian classic, once said: “Не бздо в канистру” (“Don’t chicken out!”).

Let’s live! 😊